Rev. Fr. Matey Havryliv, OSBM

Jean Gribomont, OSB, the Belgian Benedictine (1920-1986), in his essay on “Prayer according to St. Basil,”[1] claimed that the Cappadocian Hierarch had no real doctrine on this subject as such, with the one exception found in n. 37 of the Wider Rules (WR).[2] Nonetheless, Gribomont still makes a brilliant synthesis of St. Basil’s definition of prayer in its broader sense, that is:

“a spontaneous effect of love, manifesting itself by joyous delight, wonder and constant gratitude, rising above the world and ordering itself to the will of God.”[3]

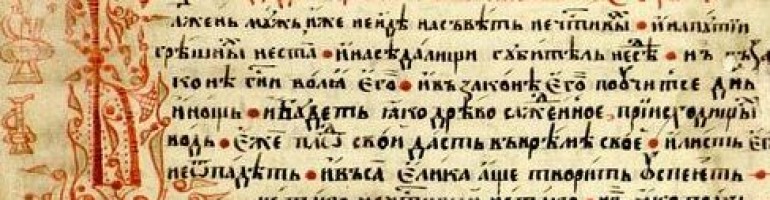

This way of prayer is perhaps best manifested in the Anaphora, in which St. Basil addresses the Creator by His own proper name – Yahweh ( Ὄ ὤν, Сый):[4]

O Existing One, Master, Lord, God, Father Almighty, Worshipped One: it is truly worthy and right to the majesty of Your holiness that we should praise You, hymn You, bless You, worship You, give thanks to You and glorify You, the only (ὄντω) truly existing ὄντα) God; and to offer You this our rational (λογικὴν) worship with a contrite heart and humble spirit, for You are He Who has graciously granted to us the knowledge of Your truth. Who is able to praise Your mighty acts? Or to make all Your praises known? Or to tell, at all times, of all your wonderful deeds?

First of all, it must be stated that St. Basil had in mind the various types of prayer as enumerated by St. Paul in his letters: “in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody… always and for everything giving thanks” (Eph 5,19; Col 3,16; 1 Tim 2,1), and also the commandment of “continuous prayer” (1 Thess. 5, 17): trying to unite the variety of human activities within a constant mindfulness of God Who sanctifies life in all its manifestations and inhabits the human person as temple.[5] In his homily “On the Martyr Julitta” and in the spirit of his previous “Dialogue on Gratitude,” St. Basil rhetorically asks and explains:

Ought we to pray without ceasing? Is it possible to obey such a command? These are questions which I see you are ready to ask. I will endeavour, to the best of my ability, to defend the charge. Prayer is a petition for what is good, addressed by the pious to God. But we do not rigidly confine our petition to words; nor do we imagine that God requires to be reminded by speech. He knows our needs even though we ask Him not. What do I say then? I say that we must not think to make our prayer complete by syllables. The strength of prayer lies rather in the purpose of our soul and in deeds of virtue thatextend to every part and moment of our lives. ‘Whether you eat,’ it is said, ‘or drink, or whatever you do, do all for the glory of God.’As you take your seat at table, pray. As you lift the loaf, offer thanks to the Giver. When you sustain your bodily weakness with wine, remember Him, Who supplies you with this gift, to make your heart glad and to comfort your infirmity. Has your hunger been satiated? Then let not the thought of your Benefactor pass away too.

As you are putting on your tunic, thank the Giver of it. As you wrap your cloak about yourself, feel yet greater love to God, Who alike in summer and in winter has given us coverings convenient for us, at once to preserve our life and to cover what is unseemly. Is the day done? Give thanks to Him Who has given us the sun for our daily work, and has provided for us a fire to light up the night, and to serve the rest of the needs of life. Let night give another occasion for prayer. When you look up to the heavens and gaze at the beauty of the stars, pray to the Lord of the visible world; pray to God the Arch-creator of the universe, Who in wisdom has made them all. When you see all nature sunk in sleep, then again worship Him Who gives us, even against our will, release from the continuous strain of toil, and by a short refreshment restores us once again to the vigour of our strength.

Let not half your life be useless through the senselessness of slumber. Divide the time of night between sleep and prayer. Let your sleep be an experience in piety; for it is only natural that our sleeping dreams should be for the most part echoes of the anxieties of the day. As have been our conduct and pursuits, so will inevitably be our dreams. Thus you will pray without ceasing; if you pray not only in words, but unite yourself to God through all the course of life and so your life is made one ceaseless and uninterrupted prayer.[6]

Thus, the Cappadocian’s understanding of prayer coincides with the explanation of Origen (185-254) as found in his work (Περιευχης – Deoratione):

Now, since the performance of actions enjoined by virtue or by the commandments is also a constituent part of prayer, he prays without ceasing who combines prayer with right actions, and virtuous actions with prayer. For the Apostolic command to “pray without ceasing” can only be accepted by us as a possibility if we speak of the whole life of a Christian as one great continuous prayer.[7]

St. Basil strongly insists that Christian life is to become prayer, and prayer is to enliven life. He emphasizes that the act of praying to God should involve all the human faculties:

The prayer of each is manifest to God; one seeks heavenly things affectionately and one seeks them learnedly; one utters his words perfunctorily with the tips of his lips, but his heart is far from God… Thus, let the tongue sing, let the mind interpret the meaning of what has been said, that you may sing with your spirit, that you may sing likewise with your mind. Not at all is God in need of glory, but He wishes us to be worthy of glory.[8]

Moreover, a person becomes prayer not merely when he continuously prays, but when he performs God’s will with love and trusting submission to his Creator.[9] Obviously, this state of prayer requires some effort and even battle against dissipation, in order “to acquire the spirit of recollection.”[10]

There is yet another dimension of prayer in St. Basil the Great, which the world renowned researcher and expert on Eastern spirituality, Cardinal Tomas Spidlík, SJ, drew our attention to, namely, the prayer of contemplation – contemplatio naturalis.[11] He writes:

As the legislator of cenobitic life, one would think that St Basil (+379) would speak first of common psalmody. However, since he was a profound contemplative, his Homily on the Hexameron[12]is an excellent guide to “natural contemplation.”[13]

Card. Spidlík does not leave out St. Basil’s thought on “prayer of the body.”[14] Indeed, the Cappadocian teacher, in his homily on Deut.15, 9, states:

Know your soul and believe in the invisible God, for just as your soul cannot be seen with physical eyes, so also God has no color, nor shape, nor bodily frame, but is perceived only through His actions. So, meditating on God, do not try to see Him with your eyes, but trust your mind and discover Him through reason. Be filled with wonder at the Artist Who joined together with such force the soul and body; the soul extends to the remotest parts of the body, tightly binding them together in harmony. Be amazed at the power the soul gives to the body, how the body senses the emotions of the soul, how the soul gives life to the body, and how the suffering of the body causes the soul to suffer.[15]

How does St. Basil regard prayer based on the Word of God, in particular, on psalmody? Obviously, as an expert on Scripture, he could not but pay attention to it. This is what he says about the vital importance of the Psalms in the life of any man:

A psalm gives profound serenity to the soul, dispensing peace, calming the tumultuous waves of thought. For it softens anger in the soul and bridles intemperance. A psalm solidifies friendships, reconciles the separated, conciliates those at enmity. Who, indeed, can consider as an enemy him with whom he has uttered the same prayer to God? So that psalmody in choral singing is a bond, as it were, of unity, joining harmoniously the people into a symphony of one choir, producing the greatest of all blessings, charity. A psalm is a city of refuge from the demons; cry for help to the angels, a shield against the fears of the night, a rest from toils of the day, a safeguard for infants, an adornment for vigorous youth, a consolation for the elderly, a most fitting ornament for women. It makes the desert a home; it moderates the excesses of the market place; it is the foundation for beginners, the improvement of those advancing, the solid support of the perfect. It is the voice of the Church, brightening feast days; it creates a sorrow which is in accordance with God. For, a psalm calls forth a tear even from a heart of stone. A psalm is the occupation of the angels, heavenly life, spiritual incense.[16]

The well-known liturgist, Fr. Robert Taft, SJ, called this union of salvation history and prayer in Scripture, which St. Basil so clearly underscored, a ‘dialectic,’ which is poured forth into the liturgy: “God acts and His people respond. Hence, the Bible is the first liturgical book of the Church.”[17]

We Basilians are especially thankful to the Holy Hierarch from Cappadocia and owe to him the precious explanation of how the Church prays seven times a day. We can see in this explanation the future structure of the Liturgy of the Hours, which subsequently evolved under the influence of various traditions.[18]

St. Basil is creative in relation to ecclesiastical rubrics, stating:

I think it is useful to pray at designated times, introducing into the fixed prayers and psalmody some change, because when the same things are repeated, our souls somehow grow cold, indifferent and dissipated. In contrast, through change and variation in psalmody and singing, at various [liturgical] times, desire and attention is renewed.

Thus, invoking Psalm 118 (119), 164, Basil states: “Seven times a day I praise You, because of Your righteous judgments.” He numbers seven as the times “designed for prayer in the monastery” and adds: “We chose them not without reason, for each one of those times reminds us, in a special way, of some divine salvific act.”[19]

| Matins | Prayers are recited early in the morning so that the first movements of the soul and the mind may be consecrated to God and that we may take up no other consideration before we have been cheered and heartened by the thought of God, as it is written: “I remembered God and was delighted” (Ps 76 (77): 4), and that the body may not busy itself with tasks before we have fulfilled the words: “To thee will I pray, O Lord; in the morning thou shalt hear my voice. In the morning I will stand before thee and will see” (Ps 5: 4-5). |

| 3rd Hour | Again at the third hour the brethren must assemble and betake themselves to prayer, even if they may have dispersed to their various employments. Recalling to mind the gift of the Spirit bestowed upon the Apostles at this third hour, all should worship together, so that they may also become worthy of receiving the gift of sanctity, and they should implore the guidance of the Holy Spirit and His instruction in what is good and useful, according to the words: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, And renew a steadfast spirit within me. Do not cast me away from Your presence, and do not take Your Holy Spirit from me. Restore to me the joy of Your salvation, and uphold me by Your generous Spirit” (Ps 50 (51): 10-12). Again, it is said elsewhere, “Your Spirit is good. Lead me in the land of uprightness” (Ps 142 (143): 10); and having prayed thus, we should again apply ourselves to our tasks. |

| 6th Hour (midday) | It is also our judgment that prayer is necessary at the sixth hour, in imitation of the saints who say: “Evening and morning and at noon I will speak and declare; and he shall hear my voice” (Ps 54 (55): 18) And so that we may be saved from invasion and the noonday Devil (Ps 90 (91): 6), at this time, also, the ninetieth Psalm will be recited. |

| 9th Hour | The ninth hour, however, was appointed as a compulsory time for prayer by the Apostles themselves in the Acts where it is related that “Peter and John went up to the temple at the ninth hour of prayer” (Acts 3: 1). |

| Vespers | When the day’s work is ended, thanksgiving should be offered for what has been granted us or for what we have done rightly therein and confession made of our omissions whether voluntary or involuntary, or of a secret fault, if we chance to have committed any in words or deeds, or in the heart itself; for by prayer we propitiate God for all our misdemeanors. |

| Complines | The examination of our past actions is a great help toward not falling into like faults again; wherefore the Psalmist says: “the things you say in your hearts, be sorry for them upon your beds” (Ps 4: 5). |

| Vigil | Again, at nightfall, we must ask that our rest be sinless and untroubled by dreams. At this hour, also, the ninetieth Psalm should be recited. Paul and Silas, furthermore, have handed down to us the practice of compulsory prayer at midnight, as the history of the Acts declares: “And at midnight Paul and Silas praised God” (Acts 16: 25). The Psalmist also says: “I rose at midnight to give praise to thee for the judgments of thy justifications” (Ps 118 (119): 62). |

“Then, too, we must anticipate the dawn by prayer,” encourages St. Basil” so that the day may not find us in slumber and in bed, according to the words: “My eyes have prevented the morning; that I might meditate on thy words” (Ps 118 (119): 148).

St. Basil does not see any reason whatsoever to neglect common psalmody; rather, he is categorical in saying: “Those, who consecrated their lives for the glory of God and the glory of Christ, must never neglect any one of those set times.”

In the case of unforeseen obstacles, St. Basil takes into account the words of Christ concerning His presence and suggests:

But, if some, perhaps, are not in attendance because the nature or place of their work keeps them at too great a distance, they are strictly obliged to carry out wherever they are, with promptitude, all that is prescribed for common observance, for “where there are two or three gathered together in my name,” says the Lord, “there am I in the midst of them” (Matt 18:20).[20]

Besides the above-listed elements of the Divine Hours, St. Basil mentions in his treatise, De Spiritu Sancto, the hymn “O Joyful Light” (Φώς ʽιλαρόν), remarking that this hymn is so ancient that no one recalls its author.[21] It is possible that Basil was also familiar with the ektenia “Angel of Peace,” citing it in his Letter 11.[22]

In our liturgical books, there are prayers attributed to St. Basil: two during the Midnight Office and “O Thou, Who in all times and places” in the First Hour and the “O Thou, Who in all times and places” in each of the other Hours and Complines.[23] There are also two prayers attributed to him, one before Holy Communion and one after Holy Communion.[24]

One should also mention two prayers in the Order of Exorcism attributed to St. Basil.[25]

As for the prayer life of St. Basil, of course, he taught by example as the Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia. We believe that even now, he continues his prayer for us, his sons and daughters, before the Throne of the Lamb. Therefore, annually honoring his memory on January 1, sing of our Founder:

Having consecrated yourself totally to God and from childhood having sacrificed yourself fully for Him, like the stars you shone of God’s wisdom and explained the nature of things, clearly teaching and wisely ordering them for a better understanding of God. So we praise you as the theological and divine teacher, and a shining beacon of the Church, and ask you pray to Christ that He would grant great mercy to the world.[26]

[1] J. Gribomont, “La preghiera secondo S. Basilio,” in La preghiera (Roma: 1964), 371-397. This same thought is held by M.Van Parys in “Memoria di Dio in Basilio di Cesarea,” 119 in Basilio tra oriente s occidente (Ed. Qiiajon, 2001), 111-125.

[2] WR = Wider Rules.

[3] J. Gribomont, “La preghiera secondo S. Basilio,” 374.

[4] For the Greek edition, Eucologio Barberini gr. 336, edited by S. Parenti and E. Velkovska, (Roma 1995), 12; for the Church-Slavonic edition, Літургіконъ сієсть Служебникъ (Римъ, 1952), 354; for the Ukrainian edition, Священна і Божественна Літургія, (Львів: Місіонер, 2003), 121.

[5] “Лист Григорія Назіанзького,” 2, 4 in Вибрані листи св. Василія Великого, 23.

[6] Migne, PG 31, 244; St. Basil, “Homily in Honour of St. Julitta,” nn. 3-4 in Науки св. Василія Великого для народу, (Glen Cove: 1954), 58-59.

[7] Origen, OnPrayer, (СПБ 1897), 43.

[8] St. Basil, “Homily on Psalm 28,” n. 7, in Науки св. Василія Великого для народу, (Glen Cove: 1954), 79-80.

[9] “Homily on the Hexameron” 2,7; 5,1 in SC 26 (1950), col. 45bc, 173ff.

[10] WR 3; cf. Аскетичні твори св. Василія Великого, trans. Metr. Andrej Sheptysky, OSBM, (Rome 1989), 132.

[11] T. Špidlik, La preghiera secondo la tradizione dell’Oriente cristiano, (Rome: Lipa, 2002), 26.

[12] SC 26bis (1968); Italian text col. 45bc, 173ff.

[13] Migne, PG 31,237-262.

[14] T. Špidlik, La preghiera secondo la tradizione dell’Oriente cristiano, 108.

[15] St. Basil, “Know Thyself!”,n.8; “Hom. In illud, Attende tibi ipsi, n. 7, PG 31, 216b.

[16] St. Basil, “Homily on Psalm 1,” n. 2, in Гомілії на Псалми, trans. Fedyniak (New York: 1979), 20.

[17] R. Taft, Oltre l’Oriente e l’Occidente, (Rome: Lipa, 1999), 256.

[18] There are many studies on this subject; see the excellent work of M. Arranz, SJ, Как молилились Богу древние византийцы, (ЛДА, 1979).

[19] WR 37; cf. Аскетичні твори св. Василія Великого, trans. Metr. Andrej Sheptysky, OSBM, (Rome 1989), 199-202.

[20] WR 37; cf. Аскетичні твори св. Василія Великого, trans. Metr. Andrej Sheptysky, OSBM, (Rome 1989), 201.

[21] De Spiritu Sancto 29,73, SC 17bis, 508-510 = PG 32, 205.

[22] St. Basil, Letters, vol. I, (Paris: Y. Courtone, 1957), 41.

[23] M. Arranz, SJ, Как молилились Богу древние византийцы, (ЛДА, 1979), 162.

[24] Ukrainian translation of these prayers in Молитовник, (Kyiv: 2001), 349-351, 356-357, 365.

[25] Требникъ Петра Могили, (Kyiv: 1646), 340-341, 343 (Kyiv: УПЦ 1996).

[26] Молитвослов, (Рим Вид-во ОО. Василіян, 1990), 795.